Every promotion should change behavior

Every piece of marketing exists for one reason: to change behavior.

Get someone to do something they weren't going to do. Get them to do something differently. Or get them to stop doing something.

Strip away the dashboards and the acronyms and the attribution models, and that's what's left. Did this change what someone did?

In eCommerce, behavior change comes down to three things:

- Make someone more likely to buy.

- Get them to buy more.

- Bring them back to buy again.

Every promotion you run should map to one of those outcomes. Not "drive revenue." Not "improve performance." Those are effects. The behavior is the cause.

Most eCommerce teams measure the effect without ever checking if the behavior actually changed.

The dashboard says yes. The margin says otherwise.

Your 10% off campaign had a 12% redemption rate and drove £50k in revenue. Your reporting calls that a success. But how much of that £50k would have come in at full price?

This is the question that separates good promotional strategy from expensive habits.

According to our research with IMRG, the average retailer generates 30% of revenue through voucher codes. That number has barely moved in five years . Customers who use codes keep using them. Customers who don't, still don't. The behaviour hasn't changed. The discount just became part of the furniture.

Look deeper, and the pattern gets more interesting.

- Affiliate-sourced codes account for 30% of all voucher usage but only 21% of voucher-code revenue.

- Native site promotions account for 33% of usage and 41% of revenue.

That gap tells you something important: not all promotional channels are changing behavior equally. Some are just giving discounts to people who were already going to buy.

The wrong question and the right one

Most promotional reporting asks: Did this offer get used?

That's the wrong question. An offer can be used without changing a single decision. Someone who was already going to buy finds a code on an affiliate site, applies it at checkout, and your attribution model records a promotional conversion. The code got used. But the behavior—the purchase—would have happened anyway.

The right question is: Did this offer change behavior?

- Did it make someone buy who otherwise wouldn't have? (More likely to buy)

- Did it get someone to add more to their basket? (Buy more)

- Did it bring someone back who had lapsed? (Buy again)

If the answer to all three is no, you didn't run a promotion. You ran a discount. And there's an important difference. A promotion is a tool for changing behavior.

A discount is a cost.

How to tell the difference

There's a simple way to start testing this, and you don't need new technology to do it.

Pick your biggest running promotion. Hold back 10% of eligible visitors so they don't see the offer. Compare conversion rates between the two groups after a week.

If the group that saw the offer converts at a meaningfully higher rate, your promotion is doing its job — it's changing behavior. If the gap is small or nonexistent, that offer is costing you margin without earning it.

This is called incrementality testing (or control group testing), and it's the single most useful thing you can do to understand whether your promotions are working or just getting used.

One outdoor retail brand ran this test over 61 days: 90% of visitors saw the promotional campaigns, 10% didn't. The result was a 15% increase in conversion rate for the group that saw the offers.

That's behavior change you can measure.

The three behaviors, applied

Once you start thinking of promotions as behavior-change tools, your strategy becomes much sharper.

Making someone more likely to buy

98% of website visitors don't buy. Not buying is the default state. The job of a conversion-focused promotion is to move someone from "not buying" to "buying." That means targeting it at people who are genuinely on the fence — showing exit intent, dwelling without acting, comparing prices elsewhere.

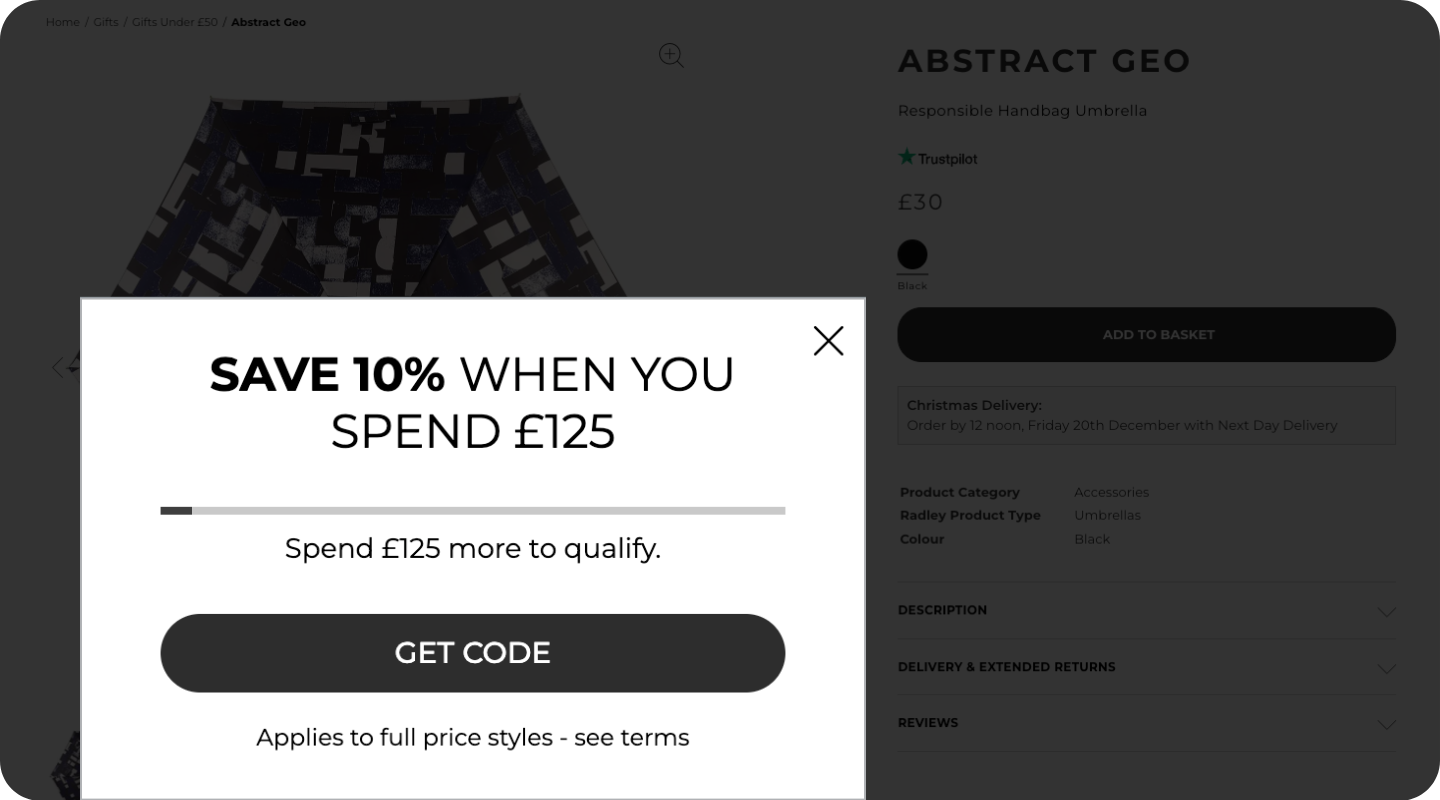

Radley ran exit campaigns alongside invalid code offers [targeting shoppers who tried codes that didn't work — a clear signal of price sensitivity]. The result was incremental revenue delivered at 8% less promotional cost than their sitewide offers. Same behavior change, lower cost.

The keyword there is "incremental." The offer didn't just get used by people who were already buying. It moved people who otherwise wouldn't have.

Getting them to buy more

This is where Stretch & Save and cross-sell campaigns live. The behavior you're changing isn't "will they buy?" — it's "how much will they buy?"

Splits59, an activewear brand, had a specific problem: customers bought bottoms but skipped the matching tops. Cross-sell campaigns targeted at outfit completion drove a 133% increase in conversion rate. The behavior changed — customers went from buying one piece to buying the set.

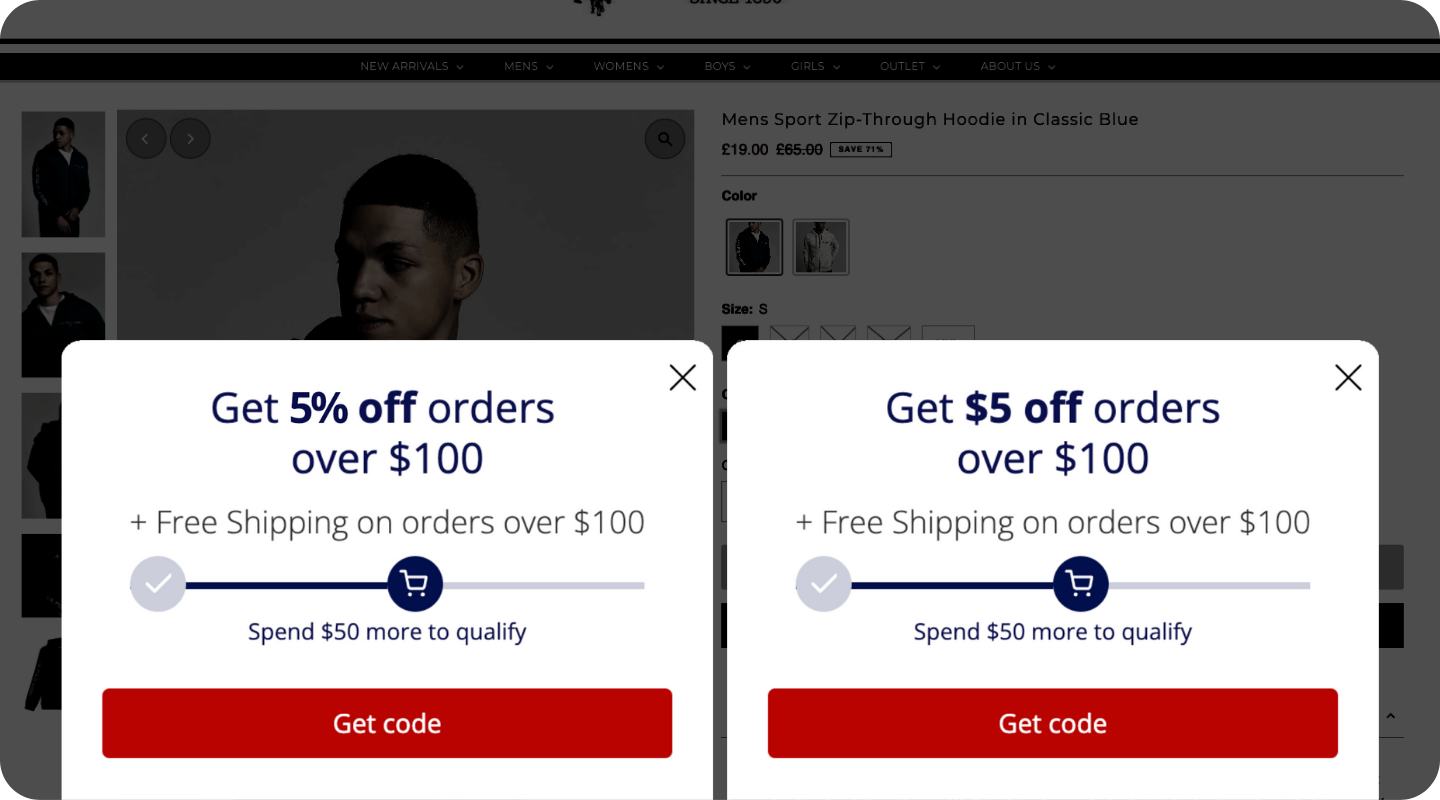

US Polo Assn tested something even more targeted: swapping "% off" for "$ off" in their Stretch & Save offers. Customers responded almost identically in terms of spend and conversion, but the fixed-dollar discount cost the brand less. Same behavior, better margin.

Bringing them back to buy again

This is the retention play, and it's where the math can be misleading. A 10% increase in repeat purchase rate sounds impressive, but unless you're a brand with naturally high repeat rates (think consumables, beauty, pet food), it rarely moves the overall revenue number as much as you'd expect.

That doesn't mean it's not worth doing. It means the behavior you're trying to change needs to be specific. A blanket "come back and get 10% off" email isn't a behavior change strategy.

A targeted offer based on what someone bought, when they bought it, and what they're likely to need next — that's a different proposition entirely.

From measurement to action

Here's a practical framework for auditing your current promotions through a behavior change lens:

- For each active promotion, ask: which behavior is this supposed to change? If the answer is vague (like "drive revenue"), the promotion probably isn't targeted enough.

- Run a simple holdout test — even 10% of traffic for one week gives you a signal.

- Compare the cost of the promotion to the incremental revenue it generates (not total revenue—incremental).

- Kill anything that doesn't pass the test, and reinvest the margin into offers that do

BCG research found that 40-60% of promotions that retailers expect to generate high ROI end up delivering low ROI.

That's not a failure of execution. It's a failure of intent. Those promotions weren't designed to change specific behaviors. They were designed to "perform." And performance without behavior change is just cost.

The shift

The best eCommerce teams are moving from "how did this promotion perform?" to "did this promotion earn its place?"

Every promotion is an investment. It costs margin. It trains customers. It sets expectations. The return on that investment isn't the redemption rate or attributed revenue. It's behavior change.

Did this make someone more likely to buy? Did it get them to buy more? Will it bring them back?

If you can answer those three questions for every promotion you run, you'll spend less on discounts and make more from the ones you keep.